PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayOur articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. For more information see out Terms and Conditions.

Historically, pronation and ‘over-pronation’ have been blamed for virtually all running injuries at some point! I even saw an example the other day where someone was told that over-pronation had caused their neck pain!

This quote from a literature review by James W. George highlights previous views;

“It has been estimated that 60% of the adult population overpronates to some degree. This overpronation accounts for 60-90% of all foot and lower extremity injuries classified as overuse conditions (4)”

[Reference 4: Cailliet, R. (1997). Foot and Ankle Pain. F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia.]

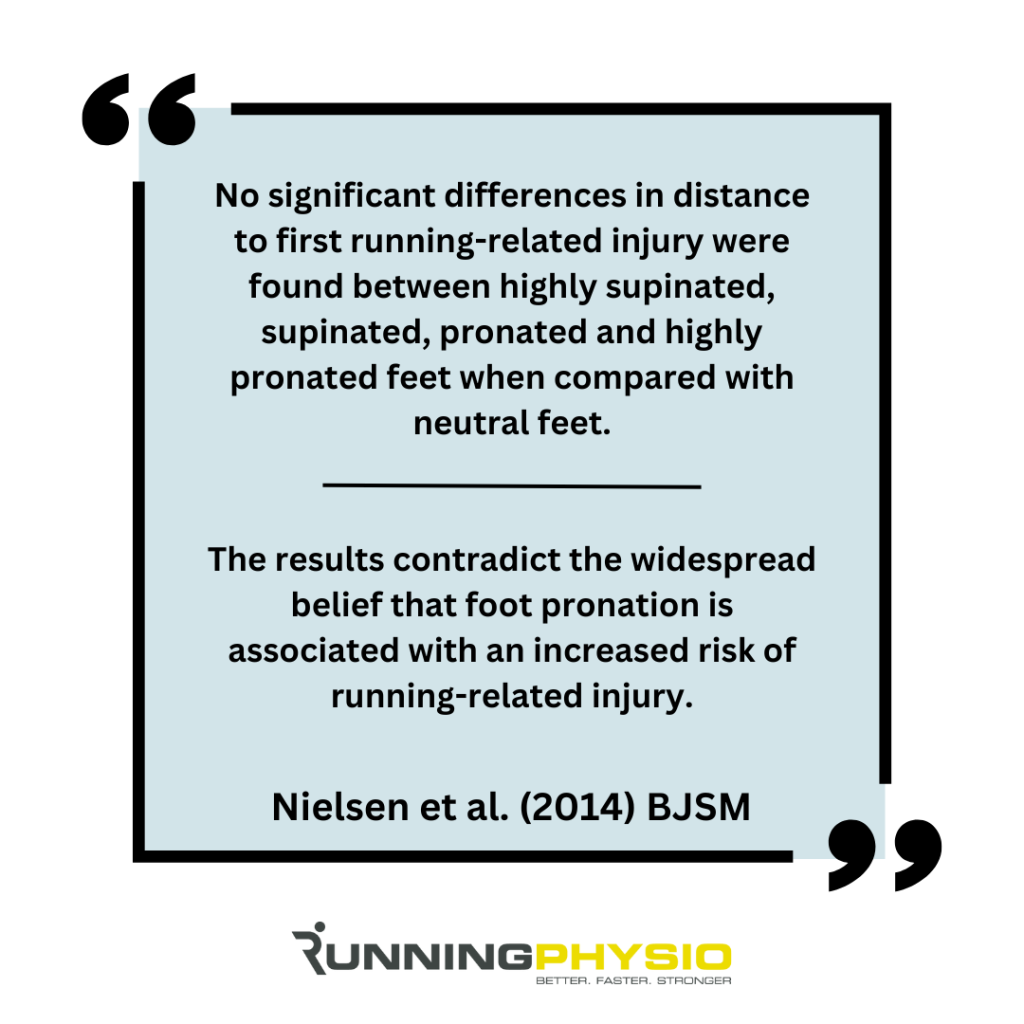

Gradually, the research has moved us away from this, especially a key paper by Neilsen et al. (2014) that studied nearly 1,000 runners. Here are a couple of quotes which summarise their findings:

This is fairly typical of ideas in sports injury. A concept is key to everything one moment, then considered irrelevant the next!

The truth usually lies somewhere in the middle and is often found by applying our clinical reasoning and the available evidence to an individual’s presentation.

Today’s email is going to help you with this by discussing dynamic assessment of pronation in runners, the bigger picture in terms of gait and potential management options (with the example of PTTD – Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction).

Dynamic assessment:

There is value in assessment of static foot posture and some evidence linking a more pronated foot type with Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome and Patellofemoral Pain (Neal et al. 2014).

However, this should be combined with dynamic assessment during running (or other goals activities) to get the full picture.

Many will focus on the endpoint of pronation when it peaks, which usually occurs at around mid-stance, but this is only really giving us half the information. We also need to see the start point and assess foot position at initial contact.

By assessing start and end position, we can see the range of pronation that needs to be controlled at the foot and ankle. This gives us a better idea of the load tissues that resist this motion (such as Tibialis Posterior) will be exposed to.

In example 1 above, I wouldn’t consider the endpoint at mid-stance to be excessively pronated, but as they land in a fairly supinated position, I’d still expect significant load on Tibialis Posterior to control that motion. Example 2 above starts in a more neutral position at initial contact but ends slightly more pronated.

Both of these examples are very normal, common findings. We don’t need to pathologise pronation! It’s not a fault. We just consider how it might influence load on sensitive tissues.

The bigger picture:

There are 3 key points to consider here:

- We might be seeing shoe motion rather than foot and ankle motion

- ’Pronation’ may be a product of other gait factors, such as step width and step rate

- When it comes to pronation, we don’t know how much is too much!

Point 1 is tricky to fix! We could remove the shoes, but that may no longer accurately represent their running style if they habitually wear them to run. It’s a limitation to consider.

Point 2 is something we can potentially change (more on that in a second). When someone runs with a narrow stride width, they will usually have more rearfoot eversion and will often land in a more supinated position (especially if forefoot striking). Note that example 1 above has a narrow stride.

A runner with a low step rate often has a longer ground contact time, which can also allow them to come into deeper pronation and dorsiflexion ranges at mid-stance.

These findings won’t be captured by static foot assessment alone.

Pronation is a normal movement that we all have to some degree. It combines with dorsiflexion and knee flexion to help us manage load during running. To my knowledge, we have no degree or range that has been established as ‘over-pronation’. But I believe this is true of other movements we might try to modify, like hip adduction or pelvic drop.

So it comes down to making a judgment and considering might this be placing more load on injured tissue. Could this be relevant to their pain? If so, then we might try a change to address it and see how symptoms respond.

Management options – example PTTD:

One pathology where we would expect pronation to be relevant would be Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction. Tibialis Posterior is a key stabiliser for the arch of the foot, and we’d expect more load on the tendon if it needs to manage larger ranges or pronation. Symptoms are usually provoked in deeper dorsiflexion, too, as we think the tendon is compressed against the medial malleolus.

With this in mind, we may try to reduce pronation and/ or dorsiflexion during running to see if that helps symptoms. There are multiple options to do this, which would be guided by the patient’s aggravating factors and response to loading activities:

- Training modifications – uphill running is likely to increase loading into dorsiflexion, and unstable services may increase demands on Tibialis Posterior, so we may suggest reducing or replacing these types of training if provocative.

- Footwear suggestions – a shoe with a larger heel-to-toe drop that has medial support and a firm heel counter (to reduce heel motion) may help reduce load on Tibialis Posterior.

- Exercise prescription – strength work for Tibialis Posterior and the calf complex may aid in load absorption and encourage tendon adaptation. It would need to be at the right level in terms of symptoms and effort, and typically we’d start out of pronated/ dorsiflexed positions (e.g. calf raise from the flat)

- Gait re-training – for a runner landing in a supinated position and therefore needing to move through a large range of pronation to bring the foot to the floor, a cue like ‘Run wider’ may help. Often, feedback is needed to prevent over-correction, but a slightly wider stance usually reduces supination at initial contact, so there’s less rearfoot motion. This can help reduce peak pronation, but a second option would be to increase step rate (if it’s low). It can help stride width and usually reduces ground contact time, so the runner doesn’t move into deeper dorsiflexion or pronation positions.

- Orthoses – my preference with orthoses is to refer to a Podiatrist for their expert input. They may suggest orthoses with a deep heel cup and heel raise (to reduce dorsiflexion) plus medial longitudinal arch support, and may include a medial wedge. The aim isn’t to correct a fault but rather to reduce painful loading of Tibialis Posterior. Taping may also be an option to consider, with similar goals in mind.

PTTD is a complex condition, and its management depends a lot on the stage and individual needs. Our suggestions here would be for stage 1 PTTD in a patient tolerating some running. They may not be appropriate for more irritable or advanced cases, such as stage 3 or 4 PTTD with fixed pes planovalgus deformity.

For more on assessment and treatment of PTTD and tendinopathy of the foot and ankle see our free Tricky Tendons series.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·